Biology begins with one fundamental question: What is life? To answer this, we study the living world, which includes all organisms that show growth, reproduction, adaptation, and response to the environment. At the same time, the living world is highly diverse – ranging from microscopic bacteria to giant trees and animals. To understand and study them, biologists use classification systems and nomenclature.

Along with this, plants form the foundation of life on Earth. In this unit, we also explore the morphology and anatomy of flowering plants, which helps us understand their structure, adaptations, and functioning.

Definition and Characteristics of Living Organisms

A living organism is any individual living thing that exhibits the properties of life. While there is no single, universally agreed-upon definition of life, scientists generally identify a set of core characteristics that, when viewed together, distinguish living organisms from non-living things.

Characteristics of Living Organisms

The primary characteristics that define a living organism are:

- Cellular Organization: All living things are composed of one or more cells, which are the fundamental units of life. This is why viruses are not considered living organisms, as they are not made of cells.

- Metabolism: Living organisms undergo metabolism, the sum of all chemical reactions that occur within them. This includes anabolism (building up complex molecules) and catabolism (breaking down molecules to release energy).

- Growth and Development: Organisms grow and develop over their lifespan, following a specific genetic blueprint. This involves an increase in size and/or number of cells and a progression toward maturity.

- Reproduction: The ability to produce offspring to ensure the continuation of a species. Reproduction can be either asexual (from a single parent) or sexual (from two parents).

- Response to Stimuli: Living organisms have the ability to sense changes in their internal or external environment and react to them. This is often called sensitivity or irritability.

- Homeostasis: For instance, in humans, body temperature is controlled by mechanisms such as sweating when it is hot or shivering when it is cold.

- Adaptation and Evolution: Living organisms have traits that allow them to survive and reproduce in their environment. These traits are a result of evolutionary adaptation over generations, which allows a species to change over time to better suit its surroundings.

Five Kingdoms of Life

The five-kingdom classification system, proposed by Robert Whittaker in 1969, categorizes all living organisms into five broad categories based on their cell structure, mode of nutrition, and body organization. This system is widely used to organize and understand the diversity of life on Earth.

Monera

The Monera kingdom includes all prokaryotic organisms, which are typically unicellular and lack a true nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. They are the most ancient and simple forms of life.

Protista

This kingdom is a diverse group of mostly unicellular eukaryotic organisms. They are a transitional group, as they are neither plants, animals, nor fungi.

Fungi

The Fungi kingdom consists of eukaryotic organisms that are typically multicellular (except for yeast, which is unicellular). They are distinct from plants because they cannot perform photosynthesis.

Plantae

The Plantae kingdom includes all plants. They are multicellular, eukaryotic, and are primarily defined by their ability to produce their own food.

Animalia

The Animalia kingdom encompasses all animals. They are multicellular, eukaryotic, and are defined by their ability to move and their heterotrophic mode of nutrition.

Morphology of Flowering Plants

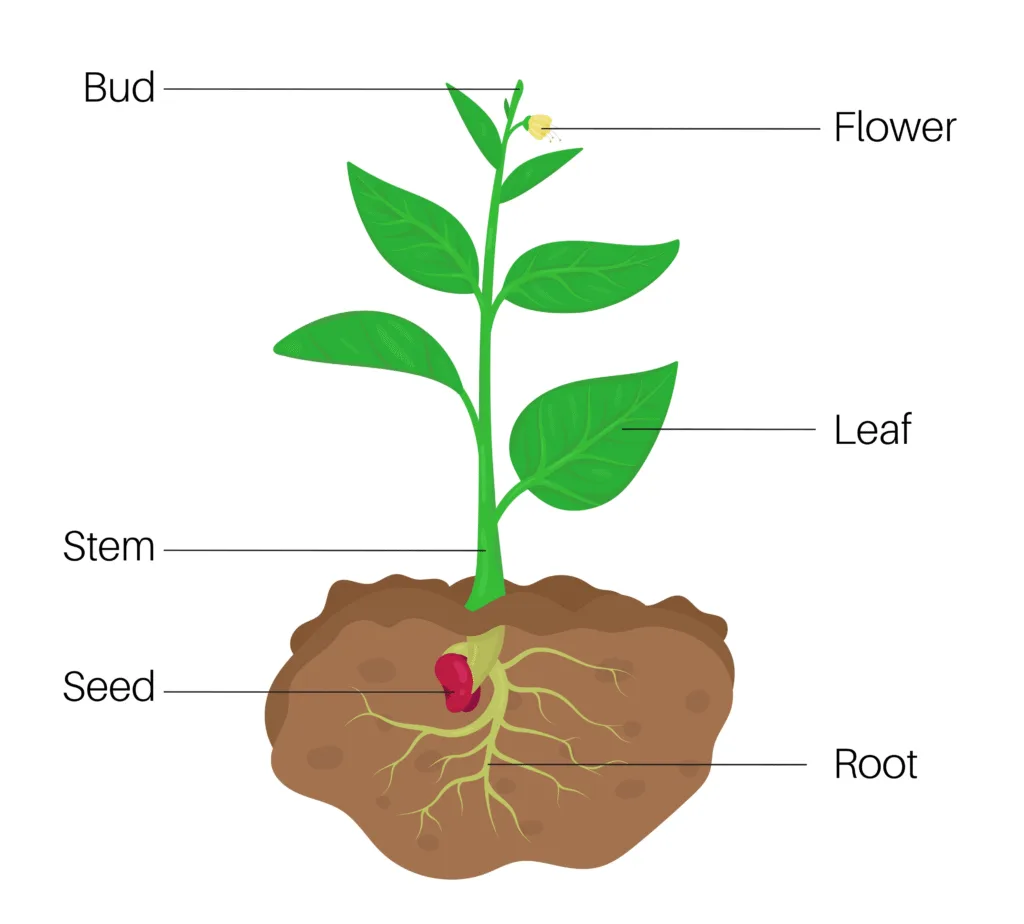

Morphology is the study of the external features and form of an organism. For flowering plants (angiosperms), morphology focuses on the structure and function of its two main systems: the root system (underground) and the shoot system (above ground).

The Root System

The root system is the subterranean part of the plant responsible for anchorage, absorption of water and minerals, and storage of food.

- Taproot System: Found mainly in dicot plants (e.g., carrots, mustard), this system has a single, thick primary root that grows deep into the soil, with smaller lateral roots branching from it.

- Fibrous Root System: Common in monocot plants (e.g., wheat, grass), this system consists of many thin, fibrous roots that grow from the base of the stem and spread out in a shallow network.

The Shoot System

The shoot system consists of the stem, leaves, flowers, fruits, and seeds.

Stem

The stem is the main axis of the shoot system, providing support for leaves, flowers, and fruits. It contains nodes, where leaves and branches grow, and internodes, the regions between the nodes. Stems can be modified for various functions, such as food storage (e.g., potato tubers) or climbing (e.g., grapevines).

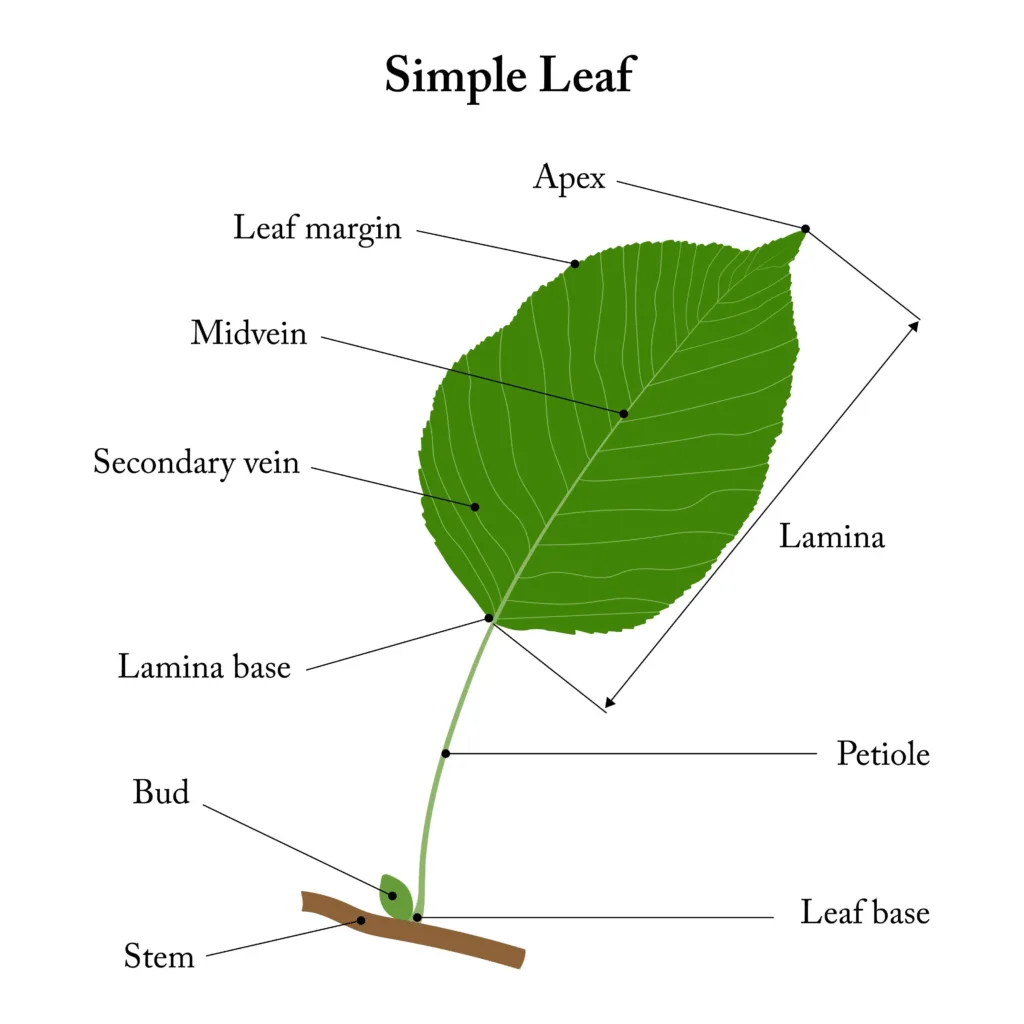

Leaf

Leaves are the primary sites for photosynthesis. They are typically flat, green structures that develop at the nodes of the stem. A typical leaf has three main parts: the leaf base, which attaches the leaf to the stem; the petiole, the stalk that holds the leaf blade; and the lamina or leaf blade, the expanded green part of the leaf.

Flower

The flower is the reproductive part of the plant. A complete flower has four main whorls:

- Calyx: The outermost whorl, made of green sepals, that protects the flower bud.

- Corolla: Made of brightly colored petals that attract pollinators.

- Androecium: The male reproductive whorl, made of stamens, which produce pollen. Each stamen has a filament and an anther.

- Gynoecium: The female reproductive whorl, made of one or more carpels or pistils. Each pistil has an ovary, a style, and a stigma.

Fruits and Seeds

After fertilization, the ovary of a flower transforms into a fruit, while the ovules inside it change into seeds. The fruit serves to safeguard the seeds and also helps in their dispersal.

General Anatomy of Monocot & Dicot Plants

The internal anatomy of monocot and dicot plants differs significantly in their roots, stems, and leaves. These differences are a result of their evolutionary development and are directly linked to their external morphology.

Anatomy of Roots

| Feature | Dicot Root | Monocot Root |

| Pith | Pith is absent or very small. | Pith is large and well-developed. |

| Vascular Bundles | Xylem and phloem are arranged in a star-like or cross shape. There are typically 2-4 xylem and phloem bundles. | Xylem and phloem bundles are arranged in a ring. There are usually more than 6 bundles (polyarch condition). |

| Secondary Growth | The cambium is present, allowing for secondary growth (increase in diameter). | Cambium is absent, so there is no secondary growth. |

Anatomy of Stems

| Feature | Dicot Stem | Monocot Stem |

| Vascular Bundles | Vascular bundles are arranged in a distinct ring. They are open, meaning they have cambium. | Vascular bundles are scattered throughout the ground tissue and are closed (without cambium). |

| Pith | A large, distinct pith is present in the center, surrounded by the ring of vascular bundles. | There is no distinct pith; the vascular bundles are scattered throughout the ground tissue. |

| Secondary Growth | Possesses cambium, enabling secondary growth and the formation of wood. | Lacks cambium, so it does not undergo secondary growth. |

| Ground Tissue | Differentiated into cortex, endodermis, pericycle, and pith. | Undifferentiated ground tissue surrounds the scattered vascular bundles. |

Anatomy of Leaves

| Feature | Dicot Leaf (Dorsiventral) | Monocot Leaf (Isobilateral) |

| Mesophyll | The tissue between the upper and lower epidermis is differentiated into two distinct layers: palisade parenchyma (upper layer of columnar cells) and spongy parenchyma (lower layer of loosely arranged cells). | The mesophyll is not differentiated. It consists of a single type of parenchymatous tissue. |

| Stomata | More stomata are found on the lower epidermis (abaxial surface) than on the upper epidermis (adaxial surface). | Stomata are present in equal or near-equal numbers on both the upper and lower epidermis. |

| Venation | Exhibits reticulate venation, with a network of veins that branch out from a central midrib. | Exhibits parallel venation, where the veins run parallel to each other. |

| Bulliform Cells | These are not typically present. | Large, empty bulliform cells are present on the upper epidermis. They help in the rolling and unrolling of leaves to reduce water loss. |