Plants, just like animals, undergo life processes such as respiration, growth, development, and cell division. Understanding these fundamental processes helps us explore how plants survive, adapt, and contribute to life on Earth.

Plant respiration

Plants respire just like other living organisms, but they do it in a unique way. Plant respiration is the process of breaking down glucose, a sugar produced during photosynthesis, to release energy for growth, maintenance, and other metabolic processes. It’s essentially the reverse of photosynthesis. While photosynthesis uses carbon dioxide and light energy to produce glucose and oxygen, respiration uses glucose and oxygen to produce carbon dioxide, water, and energy in the form of ATP.

What is Respiration?

Respiration in plants is the process by which they use the food they produce during photosynthesis to create energy for growth, development, and other metabolic activities. It is a continuous, biochemical process that occurs in all living cells of a plant, including the roots, stems, and leaves.

How Plants Respire

Unlike animals, plants do not have specialized respiratory organs like lungs. Instead, they exchange gases directly with the environment through various parts:

- Stomata: Tiny pores on the surface of leaves and green stems that open and close to regulate the exchange of gases, including oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2).

- Lenticels: Small pores on the woody parts of stems and roots that allow for gas exchange.

- Root Hairs: The roots absorb oxygen from the air pockets present in the soil.

Phases and Rate of Plant Growth

Plant growth is a complex process that occurs in three distinct phases at the cellular level:

- Meristematic Phase: This phase occurs at the root and shoot apices where cells are constantly dividing. These cells are rich in protoplasm and have large nuclei, indicating high metabolic activity.

- Elongation Phase: Cells in this region, just behind the meristematic zone, undergo rapid enlargement. Increased water uptake leads to cell expansion, and the deposition of new cell wall material contributes to the increase in size.

- Maturation Phase: In this final phase, the cells reach their maximum size and begin to differentiate and specialize to perform specific functions.

The rate of plant growth can be measured in terms of length, weight, volume, or cell number over time. When plotted against time, this growth often produces a characteristic sigmoid (S-shaped) curve representing three periods: a slow lag phase (initial growth), a rapid log or exponential phase (period of maximum growth), and a plateaued stationary phase where growth slows down or stops.

Conditions for Growth

Plant growth is significantly influenced by several external factors:

- Water: Water is essential for cell enlargement, turgor pressure, and as a medium for enzymatic activities. A lack of water can severely stunt growth.

- Oxygen: Respiration requires oxygen to release the energy needed for growth.

- Nutrients: Plants need both macro and micronutrients for proper growth and metabolism. These are absorbed from the soil.

- Temperature: Each plant has an optimal temperature range for growth. Temperatures that are too high can denature enzymes, while temperatures that are too low can slow down metabolic processes.

- Light: Light is crucial for photosynthesis, which provides the energy for growth. The intensity, quality, and duration of light all affect the rate of photosynthesis and subsequent growth.

Introduction to Plant Growth Regulators (PGRs)

Plant growth regulators, or phytohormones, are small, simple organic molecules that are naturally produced by plants and control their growth and development. They act as chemical messengers, influencing physiological processes at very low concentrations. These regulators can be broadly classified into two groups:

- Plant Growth Promoters: These hormones stimulate growth-promoting activities like cell division, cell enlargement, and organ formation. The main promoters are auxins, gibberellins, and cytokinins.

- Plant Growth Inhibitors: These hormones inhibit growth and promote dormancy and abscission (shedding of leaves or fruits). The main inhibitors are abscisic acid and ethylene. Ethylene can also act as a promoter in some cases, such as in fruit ripening.

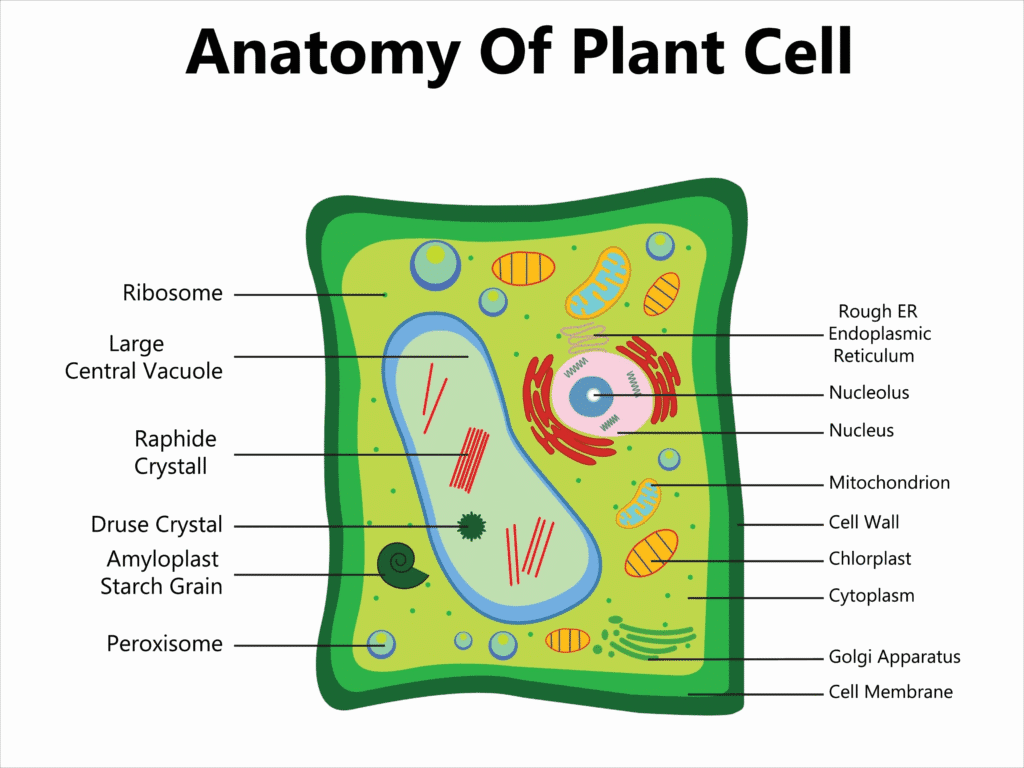

Structure and Functions of the Cell

A plant cell is a eukaryotic cell that is the basic unit of life for all plants. While it shares many organelles with animal cells, it has several unique structures that allow it to perform specific functions essential for plant life, such as photosynthesis and structural support.

Cell Organelles and Their Functions in Plants

1. Nucleus

The nucleus is the command center of the cell, housing the genetic material (DNA) in the form of chromosomes. It controls all cellular activities, including growth, metabolism, and reproduction.

2. Cell Wall

The cell wall is a rigid outer layer made of cellulose that provides structural support and protection to the cell. It maintains the cell’s shape and prevents it from bursting in a hypotonic environment.

3. Cytoplasm

The cytoplasm is the jelly-like substance that fills the cell and contains all the organelles. It is the site for many metabolic reactions, including glycolysis.

4. Cell Membrane

The cell membrane, positioned just beneath the cell wall, is a selectively permeable barrier that controls the entry and exit of substances in and out of the cell.

5. Chloroplasts

Chloroplasts are the sites of photosynthesis. They contain the green pigment chlorophyll, which captures sunlight and converts it into chemical energy (glucose).

6. Mitochondria

Mitochondria are the “powerhouses” of the cell, where cellular respiration occurs. They break down glucose to produce ATP, the cell’s primary energy currency.

7. Vacuole

Plant cells have a large, central vacuole that stores water, nutrients, and waste products. It also helps maintain turgor pressure, which keeps the plant cell rigid and upright.

8. Ribosomes

Ribosomes are responsible for protein synthesis. They can be found freely in the cytoplasm or attached to the endoplasmic reticulum.

9. Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER)

The endoplasmic reticulum is a membrane-bound network that plays a key role in the production and transport of proteins and lipids. The rough ER is studded with ribosomes, whereas the smooth ER lacks them.

10. Golgi Apparatus

The Golgi apparatus functions to modify, sort, and package proteins and lipids for delivery to their specific destinations. It is often compared to the cell’s “post office.”

11. Peroxisomes

Peroxisomes are small vesicles that carry out oxidative reactions, breaking down fatty acids and detoxifying the cell. In plants, they are also involved in photorespiration.

12. Plasmodesmata

Plasmodesmata are channels that pass through the cell walls of adjacent plant cells, allowing for direct communication and transport of substances between them.

Definition of Tissues

Plant tissues are groups of cells that are organized to perform a specific function. They are the building blocks of a plant’s organs, such as leaves, stems, and roots.

Types of Tissues

Plant tissues are classified into two main types based on the ability of their cells to divide: meristematic tissue and permanent tissue. These tissues are organized into three major systems that make up the plant body: dermal, ground, and vascular.

Meristematic Tissue

Meristematic tissues are the “growth engines” of a plant. They contain actively dividing, undifferentiated cells that are responsible for the plant’s growth in both length and girth. Meristematic cells are small, have thin cell walls, a large nucleus, and are metabolically very active. They are located in specific regions called meristems.

- Apical Meristems: Located at the tips of roots and shoots, responsible for primary growth (increase in length).

- Lateral Meristems: Found along the sides of roots and stems, responsible for secondary growth (increase in girth), which is what forms wood in trees.

- Intercalary Meristems: Located at the base of leaves and internodes, common in grasses, and responsible for the regeneration of parts removed by grazing.

Permanent Tissue

Permanent tissues are derived from meristematic tissues. Their cells have undergone differentiation to take on a specific shape, size, and function and have lost the ability to divide. They are further divided into two types:

- Simple Permanent Tissues: Made of only one type of cell.

- Parenchyma: Found in soft parts of the plant, they are involved in storage, photosynthesis, and secretion.

- Collenchyma: Provides flexible support to growing parts of the plant, like young stems and leaves.

- Sclerenchyma: Provides rigid structural support and strength to mature parts of the plant. Its cells are often dead and have thick, lignified walls.

- Complex Permanent Tissues: Made of more than one type of cell working together to perform a common function.

- Xylem: Transports water and minerals from the roots to the rest of the plant.

- Phloem: Transports food (sugars) from the leaves to other parts of the plant.